As promised in my second post on running a company, I want to talk more about time management. I’m definitely still learning myself, so while I do have useful things to say, take them with a grain of salt.

I want to start at the core of the time management problem, and work outwards from there. Before I can give any practical advice there is a question we have to ask ourselves: what is the point?

Principle #1: Know what you want.

Before there is any point to improving how you manage your time, you have to ask yourself what you want to achieve. Not only that, but you need an answer that you passionately believe in.

Similar to how exercising without a goal won’t succeed, managing time without a goal won’t either. You can join up to a gym, buy new exercise pants and book appointments with a personal trainer, but unless you actually want to achieve a defined goal (such as losing 10kg, running a marathon, or joining a sportsball team) the motivation to exercise will disappear and your exercise habit will deteriorate to nothing.

Let’s take my example. I want to better manage my time so that I spend less time on business administration and personal errands, and more time either working productively or having fun.

But it’s not just enough to have a defined goal. You have to believe in it. And for that, we need to go one step further. With exercise, you might want to run a marathon. But why would you want to do that? Because you want to feel good about your body. You don’t want to feel shame any more. And that’s good. It’s an emotional feeling, and we can latch on to emotions more than we can to abstract goals.

Personally, I want to spend more time on productive business and relaxation because those are the things I enjoy most. My work brings me joy, and so does spending time with my family and friends. Doing laundry does not. The emotional attachment I have with the people around me is the motivation I need to better manage my time.

You might have similar motivations. Or perhaps you want to get a promotion, in order to feel the higher status that brings you.

Work out what you want, and then make it feel real.

Principle #2: Time is your only resource.

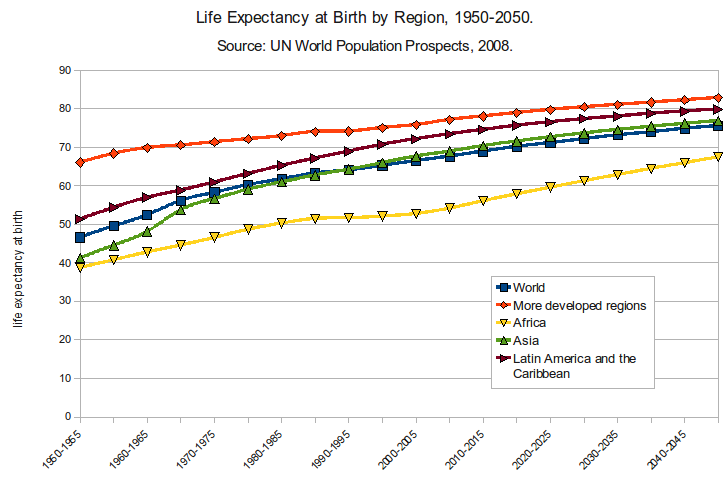

When you are born, you are gifted with roughly 67.2 years of time, which equals about 24500 days, or roughly 600,000 hours (based, of course, on where you were born and to whom).

Unless your parents were ridiculously rich, pretty much everything you have after the age of 18 was earned by yourself. Your car, your house (lucky bastard), your life partner, all these things required an investment by you. And what was the form of that investment? Time.

- When you courted your partner, you were giving up time in order to gain something more valuable (hopefully): love.

- When you bought your first car, you did so with money from your job. What is a job? Trading your time for your employer’s money.

- A house is a slightly more complex trade, but it still involves an investment of time – both before buying the house and after (both in the form of paying the mortgage and maintaining the house).

When you buy shares in a company with the hope of receiving a dividend, you’re investing your time. You spent some of your time now in order that you might have to work less (and thus have more time) in the future.

When you have a debt (like a credit card) what you really owe isn’t money: it’s the time you will have to spend to pay back the debt.

The key realisation is that time can be converted into money (most of us do it every day, in the form of a paying job), but also that money can be converted into time (by paying somebody else to do something for us). In the inter-connected global economy (fragile as it is) it’s easy to make this conversion happen both ways.

Every time you order a pizza, you’re spending your money (which you earned with your time) in order for somebody else to spend their time making a pizza in lieu of you. Because everybody is good at different things and has different prices on their time, this trade makes sense: the specialisation in the economy allows everybody to be more efficient in how they spend their time. And it’s this we will explore next.

Principle #3: What is your time worth?

Managing your time practically comes down to an issue of opportunity cost, one of the core concepts of economics. In it’s simplest form, the opportunity cost of a product or service is the sacrifice that is needed to have that product or service.

For example, a bottle of Coke is about $4. You can either have the $4 of money, or you can have the Coke. You can’t have both.

Opportunity cost is most interesting when it becomes relative. Let’s say you have a choice between going to the beach (or some other enjoyable activity) with your friends, or going to work and earning $1000. Most people would go to work, since $1000 is more valuable than the time spent with friends. Now let’s say you have the same choice, but you only earn $10. Most people would quit immediately and spend the time with their friends. Spending time with friends is worth more than $10, but less than $1000. Or is it?

What if we repeat the experiment over time? Let’s say every hour I work I earn $100. In the first hour, I’m pretty chuffed to have earned $100. I work a second hour, and I have $200. After the fourth hour I have $400, but I’m also pretty hungry. At this point I could work another hour and earn more, or I could have lunch and spend $20 (assume I’m eating out). I decide that the cost of having lunch ($120, combining both the meal cost and the lost income) is less than the cost of being hungry for another hour. Over time, our needs change and thus our opportunity costs do too.

When we do tasks like laundry or the dishes, we are saying that the cost of being able to find a clean dish or clean clothes in the future is less than the cost of having to clean them now. Whether this is true for you depends on your circumstances.

When we watch TV, we are saying that the cost of this activity is less than the cost of anything else we could do with that time (including earning more, spending time with family, running errands, etc). We have to keep in mind all the time: is this what I want to be doing with my time to the exclusion of all else?

Principle #4: Eliminate the unnecessary.

This principle is really a logical extension of the previous three principles, but it’s important enough that I’m going to include it anyway.

Given that we only have a finite amount of time, the opportunity cost of everything we do can be measured in time, and we have goals to achieve in that time, it makes sense to prioritise.

There are some things we should eliminate entirely. Logically, smoking is number one. It shortens your life, it costs you time smoking, and it costs you time working to buy cigarettes.

There are other things we might want to spend less time on, but still want to do. I enjoy watching some television, but I need to be conscious of not wasting too much time watching ABC News 24, no matter how awesome Michael Rowland is.

What we choose to eliminate and cut back on is different for everybody, because we have different goals and values in life. I don’t care about fashion, so I do only what I need to in order to look respectable. Other people enjoy fashion, so it’s a worthwhile time investment.

If something doesn’t interest you, either eliminate it from your life or figure out how to automate or outsource it.

Life is as fun and interesting as you make it.

So those are my principles of time management. From now on, in following posts, we can be a lot more practical.